For the month of February, the Brain Blog we will be covering the topic of pain. One in five adults suffer from pain globally, and approximately 1 and 5 American adults suffered from pain in 2016 (Goldberg and McGee, 2011; Dahlhamer et al., 2018). As of 2019, this translated to at least 1 billion adults living with pain, 41 million of which live in the United States. Every year, $635 billion is spent on pain management; including medical treatment and lost productivity (Gaskin & Richard, 2011). Additionally, Gold and McGee (2011) suggest pain should be treated as an issue of both public health and global social justice, asserting that, “those most disadvantaged [bear] higher burdens of persistent pain and lesser likelihood of effective treatment”. Pain is linked to mental and physical stress at work, socioeconomic status, rurality, occupational status, neighborhood, race, and education (Gold and McGee, 2011). In short, pain is not an external force acting on the body, but a distressing sensation caused by the brain and affected by other physiological and psychosocial factors (Cervero, 2014; Apkarian, Bushnell, Treede, & Zubieta, 2005; Burrell, 2017).

Additionally, Gold and McGee (2011) suggest pain should be treated as an issue of both public health and global social justice, asserting that, “those most disadvantaged [bear] higher burdens of persistent pain and lesser likelihood of effective treatment”. Pain is linked to mental and physical stress at work, socioeconomic status, rurality, occupational status, neighborhood, race, and education (Gold and McGee, 2011). In short, pain is not an external force acting on the body, but a distressing sensation caused by the brain and affected by other physiological and psychosocial factors (Cervero, 2014; Apkarian, Bushnell, Treede, & Zubieta, 2005; Burrell, 2017).

Pain involves multiple areas of the brain. Neurologically, pain is “a network of somatosensory, limbic, and associative structures receiving parallel inputs from multiple nociceptive pathways” (Apkarian et al., 2017). More simply, pain involves the activity of parts of the brain related to motor and spatial function, arousal, emotion, and memory that simultaneously receive information regarding sources of hurt from the nervous system (Apkarian et al., 2017). The process of nociceptive pain (related to injury as opposed to nerve damage or other sources of pain) begins with nerves at the site of damage. The body detects either chemical, thermal or mechanical (such as punctures or distension) damage (Swift, 2015). Local nerves then transmit this information to the spinal cord where information is then sent to different parts of the brain such as the limbic system (Swift, 2015; Apkarian et al., 2017). While nociceptive pain is common, pain can also be neuropathic (due to nerve damage), nociplastic (a reaction similar to nociceptive pain that cannot be explained by injury or environmental factors), or psychogenic (due to emotional or behavioral factors such as stress) (Board of Regents of the Univer

sity of Wisconsin, 2010; Ingraham, 2019). Pain is evolutionarily useful as “how an animal responds to such stimuli and how nociceptive stimuli impact behaviors aimed at fulfilling the drives of feeding and reproduction have considerable adaptive significance” (Burrel 2017). Pain alerts the body to sources of danger and teaches organisms to avoid injury (Crook, Dickson, Hanlon, & Walters, 2014). However, long term exposure to pain is associated with increased stress, depression, anxiety, reduced immune strength, and low energy (Cleveland Clinic, 2017).

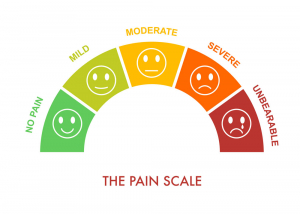

Diagnostically, pain is categorized as either chronic or acute. Experts disagree regarding the length of time used to define acute versus chronic (Turk and Okifuji, 2001). However, acute pain lasts a shorter period, anywhere from minutes to months, and ceases when the source of pain is healed. Meanwhile chronic pain lasts longer, usually weeks to years, and is not necessarily linked to an ongoing injury. While acute pain is associated with conditions that resolve quickly such as burns, headaches, post-surgical recovery, or broken bones, chronic pain is associated with conditions that take longer to resolve such as fibromyalgia and migraines. These diagnoses are usually done through pain assessment scales. However, more objective means to diagnose pain include computed tomography, magnetic resonance imagining, myelograms, electromyograms , and ultrasound imaging depending on the type of pain (Wheeler, 2019).

Pain assessment scales are the least invasive and costly means to diagnose pain but are simultaneously more subjective as they require either the patient to self-report their symptoms or their care provider to assess their discomfort. This subjectivity introduces three potential sources of bias/miscommunication: the patient’s understanding of or ability to communicate their pain or the scale, the provider’s assessment of patient pain as well as the provider’s biases regarding pain and/or the patient, and the quality, clarity, and complexity of the pain assessment scale used. The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Scale is a simple and widely used diagnostic tool designed for children that depicts five drawn faces in various degrees of pain (Wong-Baker FACES Foundation, 2016). The pros of this self-report method are that it is relatively non-verbal and simple enough that it can be used by a child. However, compared to the Brief Pain Inventory it lacks complexity in both chronology and location of the patient’s pain (Cleeland, 2009). The Neuropathic Pain Scale is also a common self-reported measure of pain that includes ranking the severity of the pain as well as describing the type of pain such as burning or tingling. However, all three of these scales still require a subjective measurement of pain, rather than using an objective measure of pain.

Objective assessments of pain can increase patient quality of life as providers can be better equipped to understand the severity of their pain. Our next article on the Brain Blog will delve further into these advances and how they relate to pain treatment. If you or a loved one are suffering from chronic pain, the International Association for the Study of Pain lists organizations worldwide committed to pain relief, or you can reach out to our Patient Advocacy program at patientadvocacy@brainsciences.org.

Written by Senia Hardwick

References

Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R.-D., & Zubieta, J.-K. (2005). Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. European Journal of Pain, 9(4), 463–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001

Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin. (2010). Classification of pain . Pain Management; Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin. http://projects.hsl.wisc.edu/GME/PainManagement/session2.4.html

Burrell, B. D. (2017). Comparative biology of pain: What invertebrates can tell us about how nociception works. Journal of Neurophysiology, 117(4), 1461–1473. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00600.2016

Cervero, F. (2014). Understanding pain: Exploring the perception of pain. MIT Press.

Cleeland, C. (2009). The Brief Pain Inventory User’s Guide. Charles S. Cleeland. https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf

Cleveland Clinic. (2017, April 3). Living with chronic pain. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/11977-chronic-pain-living-with-chronic-pain

Crook, R. J., Dickson, K., Hanlon, R. T., & Walters, E. T. (2014). Nociceptive sensitization reduces predation risk. Current Biology: CB, 24(10), 1121–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.043